On 30th October

Rachel Reeves will be setting out her first budget, rather than

responding to someone else’s decisions. She will be leading the

public discussion, not following the narrative set by another. That

will be obvious in terms of tax, because she will be raising taxes

rather than pretending to permanently cut them. But it should also be

true for the fiscal rules that she commits the government to follow.

In his first budget

of 1997, Gordon Brown set out his own fiscal rules. They were very

different from anything followed by his predecessor, and they were

innovative at the time. They lasted for ten years, derailed only by a

global crisis and the worst recession since WWII. The forthcoming

October budget is also a chance for Rachel Reeves to establish her

own fiscal rules that are better and last much longer than those of

her predecessors. [1]

Last week’s

discussion of why we have fiscal rules gives us three basic

properties that good fiscal rules should have:

-

They should

discourage politicians from using deficit finance (paying for higher

spending or lower taxes by borrowing or creating reserves (money))

simply to avoid the unpopularity of raising taxes or cutting

spending, rather than for any good economic reason. -

Conversely

they should not prevent deficit finance when this makes sense in

economic terms. For example there are good reasons why fluctuations

in public investment should be financed by borrowing, and

overwhelming reasons why a deficit financed fiscal stimulus should

be used when an economy is at risk from, in, or recovering from a

recession. -

Fiscal rules

should focus on underlying trends, rather than short or medium term

fluctuations in spending (wars, pandemics, greening the economy)

that have no strong implications for sustainability.

Fiscal rules that do

not have these properties are bad rules, and it

is better to have no fiscal rules than bad fiscal

rules.

One of the fiscal

rules that Reeves says she will follow largely has these properties,

and one clearly does not. The rule that does is sometimes called the

golden rule, and it states that in the medium term day to day public

spending (all spending except investment) should be equal to total

taxes. Specifically this involves a rolling five year ahead target

for the current budget deficit (public spending excluding public

investment minus taxes) of zero. However, as governments since

Cameron/Osborne have acknowledged, and as first proposed in Portes

and Wren-Lewis, this target has to be conditional on

the economy not being close to, in or recovering from a recession.

[2]

The conditional

golden rule achieves property (1). It achieves (2) because it doesn’t

apply during a recession, and the current balance excludes public

investment. A rolling five year ahead target helps achieve (3),

because forecasts five years ahead almost always involve the economy

being on its medium term path. It is often suggested that having a

rolling target rather than a target for a fixed date is bad because

it ‘lets politicians off the hook’. This is false, particularly

if forecasts are done by an independent body like the OBR. In

contrast having a target for a fixed date fails property (3). As we

move closer to that date fiscal policy will be responding to short

term shocks, which makes

for bad policy.

Although a

conditional medium term golden rule goes a long way to satisfying

property (3), it fails to take account of spending that is medium but

not long term. The clearest example of that today is spending that

helps the transition to green energy. For this reason, if I were

Chancellor I would task the OBR with calculating how much of the

current deficit is due to policy aimed at encouraging this green

transition, and adjust the target to exclude this spending. Any

government that lets a fiscal rule delay the green transition has got

its priorities criminally wrong.

I have seen it

recently argued that the last year of the last government showed that

deficit based fiscal rules failed, because it didn’t prevent that

government from making incredible assumptions about future spending

so it could cut taxes. That is a misunderstanding. What the fiscal

rules did, combined with an independent OBR forecast, was force the

last government to make assumptions that amounted to further

austerity in order to make tax cuts. That these plans amounted to

further austerity was widely commented on by experts in the

independent media. Without a fiscal rule and the OBR to monitor

compliance, I’m sure the last government would have claimed that it

would cut taxes and increase public spending! [3]

The other fiscal

rule that Reeves appears to have adopted, which does come from her

predecessor, is for a falling debt to GDP ratio five years ahead.

This, when you already have the golden rule, is a terrible fiscal

rule. I have not come across a single serious economist who defends

it, and plenty of eminent economists who understand the damage it is

doing (e.g FT

here, or ungated

here). The rest of this post is about all the reasons

why this rule is not fit for any purpose except keeping economic

growth down.

The first point to

make is that, if the medium term conditional golden rule is in place,

there is no need for an additional rule to achieve property (1). The

golden rule does that just fine. In that sense the falling debt to

GDP rule is completely superfluous [4]. Unfortunately that rule fails

properties (2) and (3), because it discourages much needed

investment. This is the reason I sometimes call it the suppressing

public investment rule.

Suppressing public

investment is exactly what the previous government was doing for

fourteen years, and the terrible state of our public sector is partly

a result of that. This was perhaps why that government was so

attached to this rule. In contrast, Reeves has spoken many times

about the need for additional public investment, so it makes no

economic sense for her to adopt a rule designed to suppress that

investment.

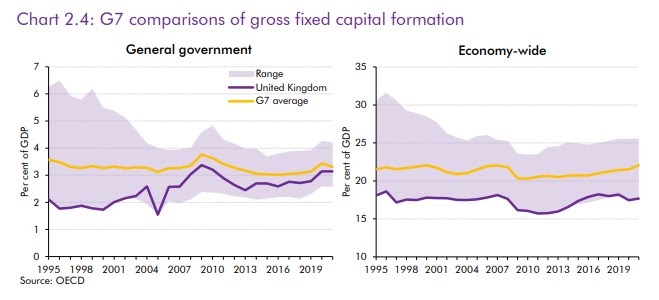

We currently need a

surge in public investment to catch up all the ground we have lost.

But the case for much higher public investment is even stronger than

that, as recent

research from the OBR clearly shows. Their paper first

shows how public and private investment are really low in the UK

compared to other G7 countries.

Public investment

began rising towards the G7 average in the first decade of this

century, but austerity cuts set that back. Private investment is no

better, but that is partly because public and private investment are

often complements.

The OBR, using very

reasonable assumptions, calculates that if public investment was

increased by 1% of GDP permanently, potential output would be 0.4%

higher after 5 years. The impact on potential output goes on rising

steadily, to reach 2.4% after 50 years. The paper also looks at what

these assumptions imply for average rates of return and benefit to

cost ratios. Of course the whole point of a good investment strategy

is to choose individual projects that have a high return, and make

sure these projects are not thwarted by some archaic fiscal rule.

What the OBR’s analysis shows clearly is that increasing public

investment is an excellent way to help improve the UK’s recently

dire growth performance.

The falling debt to

GDP rule is classic mediamacro. It comes from the idea that

government debt is a ‘bad thing’ by making false and selective

comparisons to household debt, that current levels are ‘obviously’

too high, and so debt needs to be brought down. It’s a rule that

economists advise against but political advisers say is essential to

maintain ‘political credibility’, which is code for what

non-economists in the media think should happen. Everyone from

political journalists to the great and the good like to opine about

fiscal rules while having little knowledge. It is they, not

economists, the markets or even

GOD, that think maintaining such a bad fiscal rule is essential

for credibility, and they are wrong about this just as they were

wrong about 2010 austerity.

Reeves should take

the opportunity of her first budget to consign this rule to the

dustbin. The new OBR analysis of public investment provides the

perfect excuse to do so, if she needed an excuse. [5] A comment from the National Institute argues that the OBR’s analysis may underestimate the impact of public investment on economic growth.

What should take its

place as Reeves’ second fiscal rule? Nothing. You don’t need a

second fiscal rule. It serves no purpose, beyond the bad one of

suppressing useful public investment. As

I argued here, replacing it with a target for falling

net public sector worth to GDP is just double counting. It makes

sense to look at public sector net worth when looking at

sustainability over the longer term (beyond five years), but having

it as part of a fiscal rule is not sensible.

Yes, the

Conservative opposition will claim that abandoning the falling debt

to GDP rule allows the Chancellor to have slightly higher spending

(about half a percentage point of GDP, according to the last OBR

forecast) and higher public investment. Most voters will be happy

about that. No one in the bond market will be worried – why should

they be, when the OBR calculates that public investment almost pays

for itself in generating higher taxes. [6] Much more importantly,

abandoning this rule will allow the Chancellor to expand public

investment to boost economic growth and green the economy. Getting

rid of the falling debt to GDP rule is really a no-brainer for any

Chancellor whose main concern is the health of the economy rather

than what the media commentariat might say.

[1] Part of the

cynicism surrounding fiscal rules is a consequence of the last

government, which changed fiscal rules even more frequently than the

Prime Minister. Sometimes this wasn’t because the rules they

replaced would have been broken, but just as a political ploy to

wrongfoot the opposition. Essentially the last government used the

misconceived media credibility they got from austerity to devalue the

concept of a fiscal rule.

[2] Formally, the

lower bound for nominal interest rates makes it essential that we

have fiscal stimulus to prevent, moderate or recover from a

recession. The exact form this conditionality takes is a second

order, though important, problem.

[3] There is an

issue about the OBR being forced to make forecast assumptions it

strongly suspects are false, which I

discussed here. This is an issue about the OBR’s mandate, not about fiscal rules.

[4] In fact the

falling debt to GDP rule has nothing to do with the basic principle

of ensuring debt sustainability. Instead it is based on the

presumption that the current debt to GDP ratio is too high, and as I

discussed in my previous post there is no evidence for this.

[5] If Reeves is

planning to keep this silly rule, and has already adjusted her plans

so that the rule is met, it is not too late. She could be politically

clever and announce both the end of this rule, but also that her

fiscal plans would have met the rule anyway, showing that the rule is

being ditched on good economic grounds rather than so she can spend

more or tax less.

[6] That doesn’t mean that long term interest rates will not rise. They may if additional public investment adds to already strong aggregate demand (in the face of weak aggregate supply), and markets anticipate that this will put upward pressure on interest rates. The obvious way to avoid that is to increase taxes.